An diofar eadar na mùthaidhean a rinneadh air "Minding Your Ps and Qs or Why Porcom is a Headache"

| (47 mùthadh eadar-mheadhanach le 2 chleachdaiche eile nach eil 47 'gan sealltainn) | |||

| Loidhne 1: | Loidhne 1: | ||

| − | Today we'll take just a little dip into the history of Gaelic which starts about | + | Today we'll take just a little dip into the history of Gaelic which starts about 5000 BC, so fasten your seatbelts. |

==The horrible history== | ==The horrible history== | ||

| − | 5000 BC is roughly when the first Indo-Europeans | + | 5000 BC is roughly when the first Indo-Europeans started invading Europe. We say "invading" because we know people were there before them. Amongst this lovely bunch of hooligans, from the steppes of Central Asia, there was a group which settled on the northern edges of the Alps. The Celts. Back then, they weren't known as the Celts and the two earliest "Celtic cultures", that we know about, are often called the Hallstatt and the La Tène Cultures. Irrespective of the naming issue, this bunch did well and by the 3rd century AD they'd established quite a track record. They muscled the Etruscans out of most of northern Italy, had taken over most of Gaul as well as large swathes of the Iberian peninsula, Southern Germany, the British Isles, parts of modern day Slovenia, Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, a fair chunk of land in central Turkey(!), sacked Delphi in 279 BC and Rome, itself, in 390 BC. |

| − | Incidentally, it's from the Greeks that the Celts | + | Incidentally, it's from the Greeks that the Celts got their name. The historian, Hecataeus, described them as <span style="color: #6600CC;">Keltoi</span>, the meaning of which can not be absolutely ascertained. But, seeing that they sacked Delphi, it can't have meant anything nice. |

| − | However, after that, the Celts | + | However, after that, the Celts slipped a bit. In 192 B.C., Rome took back Transalpina and gradually took over... well ... really most of Europe and the decline of the Celts began. |

==Indo-European== | ==Indo-European== | ||

So what about the language? Patience! The main thing that distinguished the Celts from other Indo-Europeans, in terms of their language, was the loss of Indo-European p. Pardon? Well, Indo-European, which is not recorded, but reconstructed based on what we know of its daughter languages, seems to have had an elaborate system of stops, 12 of them: | So what about the language? Patience! The main thing that distinguished the Celts from other Indo-Europeans, in terms of their language, was the loss of Indo-European p. Pardon? Well, Indo-European, which is not recorded, but reconstructed based on what we know of its daughter languages, seems to have had an elaborate system of stops, 12 of them: | ||

| − | {| | + | {| class="wikitable" width="30%" align="center" |

|- | |- | ||

| p || t || k || kʷ | | p || t || k || kʷ | ||

| Loidhne 22: | Loidhne 22: | ||

==Celtic== | ==Celtic== | ||

| − | Now we come to Celtic, very old Celtic | + | Now we come to Celtic, meaning very old Celtic. Those speakers decided to drop the entire set of aspirated voiced stops and made do with just 8 stops: |

| − | {| | + | {| class="wikitable" width="30%" align="center" |

|- | |- | ||

| p || t || k || kʷ | | p || t || k || kʷ | ||

| Loidhne 32: | Loidhne 32: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | One thing you need to know about that little superscript ʷ is that it represents something called labialisation. It means that you round your lips when making that sound, like in the English word ''quick'' which is [kʷɪk]. This is important. Why? You'll see. | |

==Late Common Celtic== | ==Late Common Celtic== | ||

| − | Next, for whatever reason, Late Common Celtic | + | Next, for whatever reason, Late Common Celtic dropped p and said k wherever there was a p before. It just does. That leaves us with: |

| − | {| | + | {| class="wikitable" width="30%" align="center" |

|- | |- | ||

| || t || k || kʷ | | || t || k || kʷ | ||

| Loidhne 44: | Loidhne 44: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | ||

==Goidelic and Brythonic== | ==Goidelic and Brythonic== | ||

| − | + | Then things got interesting because this was roundabout the time when Goidelic (the granfer of Irish, Gaelic and Manx) and Brythonic (granma of Welsh, Cornish, Cumbric and Breton) put in for a divorce. Over a p. What happened is that Brythonic took the kʷ sound and turned it into a p. That works because labialisation is made with the lips and there seems to have been a struggle between the labial nature of the ʷ and the velar nature of the k. It appears that the lips won and the k bit was assimilated into a p. It's like the word ''immigrate'' which comes from <span style="color: #6600CC;">in-migrāre</span> where the n has been assimilated into an m because it is immediately followed by one. | |

| − | Goidelic on the other hand would have none of it and | + | Goidelic on the other hand would have none of it and did not redevelop the p. However, out of sheer spite, it merged the labial series with the plain stops so that kʷ merged with k and gʷ with g. |

| − | + | So, this in Goidelic: | |

| − | {| | + | {| class="wikitable" align="center" |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | style="width: 50pt;" | |

| + | | style="width: 50pt;" | t | ||

| + | | style="width: 50pt;" | k | ||

| + | | style="width: 50pt;" | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | b || d || g | + | | b || d || g || |

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | But in Brythonic: | + | But, this in Brythonic: |

| − | {| | + | {| class="wikitable" align="center" |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | style="width: 50pt;" | |

| + | | style="width: 50pt;" | t | ||

| + | | style="width: 50pt;" | k | ||

| + | | style="width: 50pt;" | p | ||

|- | |- | ||

| b || d || g || gʷ | | b || d || g || gʷ | ||

| Loidhne 71: | Loidhne 77: | ||

==So what?== | ==So what?== | ||

| − | This is the reason for a great many things. For example, it is the reason why Goidelic is sometimes referred to as Q-Celtic and Brythonic as P-Celtic. It's based on the development of the Indo-European word for 5, penkʷe which in Q-Celtic becomes cóic (remember, Goidelic dropped p) and in Brythonic pimp (remember, Brythonic kept p). That explains the P but not the Q. Well, it does explain it in Manx because cóig is spelled queig. | + | This is the reason for a great many things. For example, it is the reason why Goidelic is sometimes referred to as Q-Celtic and Brythonic as P-Celtic. It's based on the development of the Indo-European word for 5, <span style="color: #6600CC;">penkʷe</span> which in Q-Celtic becomes <span style="color: #6600CC;">cóic</span> (remember, Goidelic dropped p) and in Brythonic <span style="color: #6600CC;">pimp</span> (remember, Brythonic kept p). That explains the P but not the Q. Well, it does explain it in Manx because <span style="color: #008000;">cóig</span> is spelled <span style="color: #6600CC;">queig</span>. |

So, what else does it explain? It explains why modern Brythonic languages have a gap - meaning there's no historic [kw] sound which explains why they have [p] where modern Goidelic languages have a [k]: | So, what else does it explain? It explains why modern Brythonic languages have a gap - meaning there's no historic [kw] sound which explains why they have [p] where modern Goidelic languages have a [k]: | ||

{| style="width: 70%;" border="0" align="center" | {| style="width: 70%;" border="0" align="center" | ||

| − | | || Indo-European || | + | | || Indo-European || from || Gaelic || Irish || Manx || Welsh || Cornish || Breton |

| + | |- | ||

| + | | five || IE <span style="color: #6600CC;">penkʷe</span> || || <span style="color: #008000;">cóig</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">cúig</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">queig</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">pump</span> ||<span style="color: #6600CC;">pymp</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">pemp</span> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | head || ? || || <span style="color: #008000;">ceann</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">ceann</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">qione</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">pen</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">penn</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">penn</span> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | sense || ? || || <span style="color: #008000;">ciall</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">ciall</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">keeaill</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">pwyll</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">poell</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">poell</span> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | who || IE <span style="color: #6600CC;">kʷos</span> || || <span style="color: #008000;">có</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">cé</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">quoi</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">pwy</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">piw</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">piv</span> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | wool/feather || IE <span style="color: #6600CC;">petna</span> || Lat. <span style="color: #6600CC;">plūma</span> || <span style="color: #008000;">clòimh</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">clúmh</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">clooie</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">plufyn</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">pluvenn</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">plu</span> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | Pict || prob. a Common Celtic form *kʷritan- || || <span style="color: #008000;">Cruithneach</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">Cruithneach</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;"></span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">Pryden</span> ||<span style="color: #6600CC;"></span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;"></span> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | It also explains some lovely loanwords like <span style="color: #008000;">Càisg</span> for Easter which is derived from ecclesiastical Latin <span style="color: #6600CC;">Pascha</span> (cf. Sp. <span style="color: #6600CC;">Pasqua</span>). Even some relatively late loans show this change, such as Norse <span style="color: #6600CC;">upsi</span> ''mature saithe'' which was borrowed as <span style="color: #6600CC;">ugsa</span> (and in some areas then metathesized to <span style="color: #6600CC;">ucas</span>). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Here's a list: | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable sortable" border="1" | ||

| + | |+ Latin loans with a p » c change | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! scope="col" | Latin | ||

| + | ! scope="col" | Meaning | ||

| + | ! scope="col" | Gaelic | ||

| + | ! scope="col" | Irish | ||

| + | ! scope="col" | Manx | ||

| + | ! scope="col" | Notes | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <span style="color: #6600CC;">pallium</span> || veil || <span style="color: #008000;">caille</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">caille</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;"></span> || More common than <span style="color: #008000;">caille</span> is the derived term <span style="color: #008000;">'''caille'''ach</span>, originally in the sense of ''veiled one'' | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <span style="color: #6600CC;">Pascha</span> || Easter || <span style="color: #008000;">Càisg</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">Cáisc</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">Caisht</span> || | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <span style="color: #6600CC;">planta</span> || shoot, sprout || <span style="color: #008000;">clann</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">clann</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">cloan</span> || Via Old Irish <span style="color: #6600CC;">cland</span>. This Latin word has also gone into Welsh <span style="color: #6600CC;">plant</span> (of course retaining the p), also with the meaning 'children', but interestingly not Cornish or Breton. | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | <span style="color: #6600CC;">plectere</span> || to weave, braid || <span style="color: #008000;">cleachd</span> (n. braid, tress) || <span style="color: #6600CC;">cleacht</span> (n. plait) || <span style="color: #6600CC;">claight</span> || |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | <span style="color: #6600CC;">plūma</span> || feather || <span style="color: #008000;">clòimh</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">clúmh</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">clooie</span> || |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | <span style="color: #6600CC;">premiter</span> || presbyter || <span style="color: #008000;">cruimhthear </span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">cruimhthir</span> || || |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | <span style="color: #6600CC;">purpura</span> || purple || <span style="color: #008000;">corcar</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">corcra</span> || || |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | <span style="color: #6600CC;">puteus</span> || pit, dungeon || <span style="color: #008000;">cuithe</span> || <span style="color: #6600CC;">cuithe</span> || || |

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | It also | + | Occasionally this seems to involve a p/g change, like in <span style="color: #008000;">giseag</span> which also shows up as <span style="color: #008000;">piseag</span> - the same word as Irish <span style="color: #6600CC;">piseog</span> which was borrowed into English as ''pishogue''. This shows up in Middle Irish as <span style="color: #6600CC;">piseóc, pisóc</span> with pretty much the same meaning. |

| + | |||

| + | It also makes for a headache because modern Irish and Gaelic, as we have just seen, do not retain the kʷ sound but sometimes borrow words from English which has kʷ. How to borrow? Do you borrow the sound kʷ and change the set of sounds in these languages? Or, do you adjust to Irish/Gaelic spelling? Or, do you try to come up with your own word? Tricky one. Traditionally, the second option seems to have prevailed. For example, Irish borrowed Quaker as <span style="color: #6600CC;">Caecar</span> and Gaelic turned a quadruped into <span style="color: #008000;">ceithir-chasach</span>. But, lately, words like <span style="color: #6600CC;">quinín</span> 'quinine' have showed up in Irish and Gaelic now boasts <span style="color: #008000;">cuaraidh</span> for 'quarry' and <span style="color: #008000;">cuòta</span> for 'quota'. Really tricky one. | ||

| − | + | So, what on earth then is <span style="color: #6600CC;">porcom</span>? Well, in the Mesopotamian clay table of Ashur-Bannipal... just kidding. There is a 3rd century inscription in Lusitanian, a language spoken in the west of the Iberian peninsula and which is generally described as Celtic, and it goes: | |

| − | + | <span style="color: #6600CC;">OILAM TREBOPALA INDI PORCOM LAEBO</span> | |

| − | + | etc. etc. The tricky bit is that it translates as "a sheep to Trebopala and a pig to Laebo'. And, as we all know, the great clue to something being an old Celtic language is the loss of p '''before''' the stage where Brythonic reinvents it. Yet, here we have <span style="color: #6600CC;">porcom</span> 'pig' ... The answer? Actually, we don't have an answer except that there may be a question mark over Lusitanian being a Celtic language. If you find out, publish and you'll be famous! | |

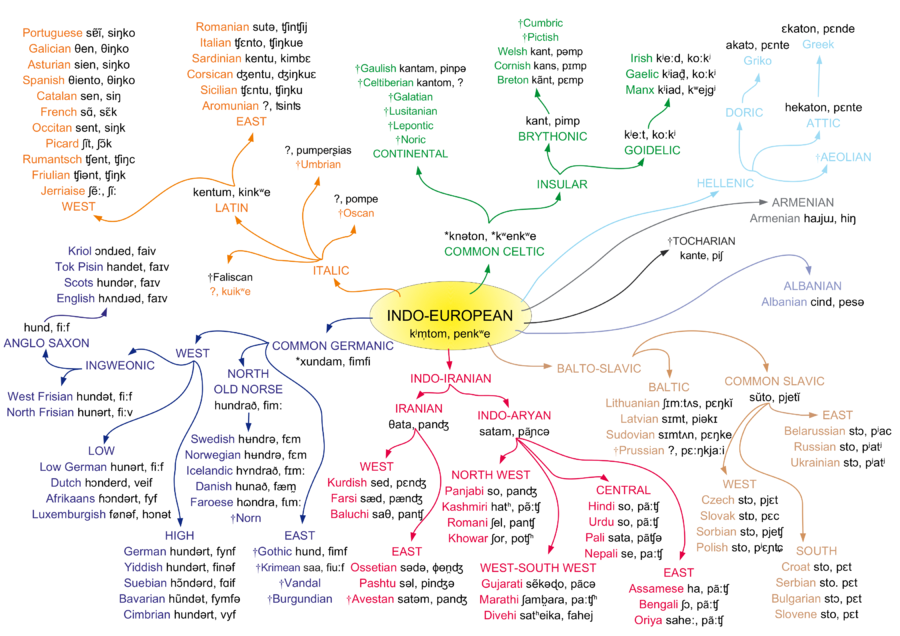

| − | + | Oh, and in case this kind of thing fascinates you, we've made a little picture for you of what happened to two words - hundred and five - all the way from Indo-European down to over 50 modern Indo-European languages here: | |

| − | + | [[Faidhle:Five and Hundred in Indo European.png|thumb|center|900px]] | |

<br /> | <br /> | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

{{BeaganGramair}} | {{BeaganGramair}} | ||

Mùthadh on 12:56, 14 dhen Chèitean 2020

Today we'll take just a little dip into the history of Gaelic which starts about 5000 BC, so fasten your seatbelts.

The horrible history

5000 BC is roughly when the first Indo-Europeans started invading Europe. We say "invading" because we know people were there before them. Amongst this lovely bunch of hooligans, from the steppes of Central Asia, there was a group which settled on the northern edges of the Alps. The Celts. Back then, they weren't known as the Celts and the two earliest "Celtic cultures", that we know about, are often called the Hallstatt and the La Tène Cultures. Irrespective of the naming issue, this bunch did well and by the 3rd century AD they'd established quite a track record. They muscled the Etruscans out of most of northern Italy, had taken over most of Gaul as well as large swathes of the Iberian peninsula, Southern Germany, the British Isles, parts of modern day Slovenia, Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, a fair chunk of land in central Turkey(!), sacked Delphi in 279 BC and Rome, itself, in 390 BC.

Incidentally, it's from the Greeks that the Celts got their name. The historian, Hecataeus, described them as Keltoi, the meaning of which can not be absolutely ascertained. But, seeing that they sacked Delphi, it can't have meant anything nice.

However, after that, the Celts slipped a bit. In 192 B.C., Rome took back Transalpina and gradually took over... well ... really most of Europe and the decline of the Celts began.

Indo-European

So what about the language? Patience! The main thing that distinguished the Celts from other Indo-Europeans, in terms of their language, was the loss of Indo-European p. Pardon? Well, Indo-European, which is not recorded, but reconstructed based on what we know of its daughter languages, seems to have had an elaborate system of stops, 12 of them:

| p | t | k | kʷ |

| b | d | g | gʷ |

| bʰ | dʰ | gʰ | gʷʰ |

Celtic

Now we come to Celtic, meaning very old Celtic. Those speakers decided to drop the entire set of aspirated voiced stops and made do with just 8 stops:

| p | t | k | kʷ |

| b | d | g | gʷ |

One thing you need to know about that little superscript ʷ is that it represents something called labialisation. It means that you round your lips when making that sound, like in the English word quick which is [kʷɪk]. This is important. Why? You'll see.

Late Common Celtic

Next, for whatever reason, Late Common Celtic dropped p and said k wherever there was a p before. It just does. That leaves us with:

| t | k | kʷ | |

| b | d | g | gʷ |

Goidelic and Brythonic

Then things got interesting because this was roundabout the time when Goidelic (the granfer of Irish, Gaelic and Manx) and Brythonic (granma of Welsh, Cornish, Cumbric and Breton) put in for a divorce. Over a p. What happened is that Brythonic took the kʷ sound and turned it into a p. That works because labialisation is made with the lips and there seems to have been a struggle between the labial nature of the ʷ and the velar nature of the k. It appears that the lips won and the k bit was assimilated into a p. It's like the word immigrate which comes from in-migrāre where the n has been assimilated into an m because it is immediately followed by one.

Goidelic on the other hand would have none of it and did not redevelop the p. However, out of sheer spite, it merged the labial series with the plain stops so that kʷ merged with k and gʷ with g.

So, this in Goidelic:

| t | k | ||

| b | d | g |

But, this in Brythonic:

| t | k | p | |

| b | d | g | gʷ |

So what?

This is the reason for a great many things. For example, it is the reason why Goidelic is sometimes referred to as Q-Celtic and Brythonic as P-Celtic. It's based on the development of the Indo-European word for 5, penkʷe which in Q-Celtic becomes cóic (remember, Goidelic dropped p) and in Brythonic pimp (remember, Brythonic kept p). That explains the P but not the Q. Well, it does explain it in Manx because cóig is spelled queig.

So, what else does it explain? It explains why modern Brythonic languages have a gap - meaning there's no historic [kw] sound which explains why they have [p] where modern Goidelic languages have a [k]:

| Indo-European | from | Gaelic | Irish | Manx | Welsh | Cornish | Breton | |

| five | IE penkʷe | cóig | cúig | queig | pump | pymp | pemp | |

| head | ? | ceann | ceann | qione | pen | penn | penn | |

| sense | ? | ciall | ciall | keeaill | pwyll | poell | poell | |

| who | IE kʷos | có | cé | quoi | pwy | piw | piv | |

| wool/feather | IE petna | Lat. plūma | clòimh | clúmh | clooie | plufyn | pluvenn | plu |

| Pict | prob. a Common Celtic form *kʷritan- | Cruithneach | Cruithneach | Pryden |

It also explains some lovely loanwords like Càisg for Easter which is derived from ecclesiastical Latin Pascha (cf. Sp. Pasqua). Even some relatively late loans show this change, such as Norse upsi mature saithe which was borrowed as ugsa (and in some areas then metathesized to ucas).

Here's a list:

| Latin | Meaning | Gaelic | Irish | Manx | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pallium | veil | caille | caille | More common than caille is the derived term cailleach, originally in the sense of veiled one | |

| Pascha | Easter | Càisg | Cáisc | Caisht | |

| planta | shoot, sprout | clann | clann | cloan | Via Old Irish cland. This Latin word has also gone into Welsh plant (of course retaining the p), also with the meaning 'children', but interestingly not Cornish or Breton. |

| plectere | to weave, braid | cleachd (n. braid, tress) | cleacht (n. plait) | claight | |

| plūma | feather | clòimh | clúmh | clooie | |

| premiter | presbyter | cruimhthear | cruimhthir | ||

| purpura | purple | corcar | corcra | ||

| puteus | pit, dungeon | cuithe | cuithe |

Occasionally this seems to involve a p/g change, like in giseag which also shows up as piseag - the same word as Irish piseog which was borrowed into English as pishogue. This shows up in Middle Irish as piseóc, pisóc with pretty much the same meaning.

It also makes for a headache because modern Irish and Gaelic, as we have just seen, do not retain the kʷ sound but sometimes borrow words from English which has kʷ. How to borrow? Do you borrow the sound kʷ and change the set of sounds in these languages? Or, do you adjust to Irish/Gaelic spelling? Or, do you try to come up with your own word? Tricky one. Traditionally, the second option seems to have prevailed. For example, Irish borrowed Quaker as Caecar and Gaelic turned a quadruped into ceithir-chasach. But, lately, words like quinín 'quinine' have showed up in Irish and Gaelic now boasts cuaraidh for 'quarry' and cuòta for 'quota'. Really tricky one.

So, what on earth then is porcom? Well, in the Mesopotamian clay table of Ashur-Bannipal... just kidding. There is a 3rd century inscription in Lusitanian, a language spoken in the west of the Iberian peninsula and which is generally described as Celtic, and it goes:

OILAM TREBOPALA INDI PORCOM LAEBO

etc. etc. The tricky bit is that it translates as "a sheep to Trebopala and a pig to Laebo'. And, as we all know, the great clue to something being an old Celtic language is the loss of p before the stage where Brythonic reinvents it. Yet, here we have porcom 'pig' ... The answer? Actually, we don't have an answer except that there may be a question mark over Lusitanian being a Celtic language. If you find out, publish and you'll be famous!

Oh, and in case this kind of thing fascinates you, we've made a little picture for you of what happened to two words - hundred and five - all the way from Indo-European down to over 50 modern Indo-European languages here:

| Beagan gràmair | ||||||||||||

| ᚛ Pronunciation - Phonetics - Phonology - Morphology - Tense - Syntax - Corpus - Registers - Dialects - History - Terms and abbreviations ᚜ | ||||||||||||